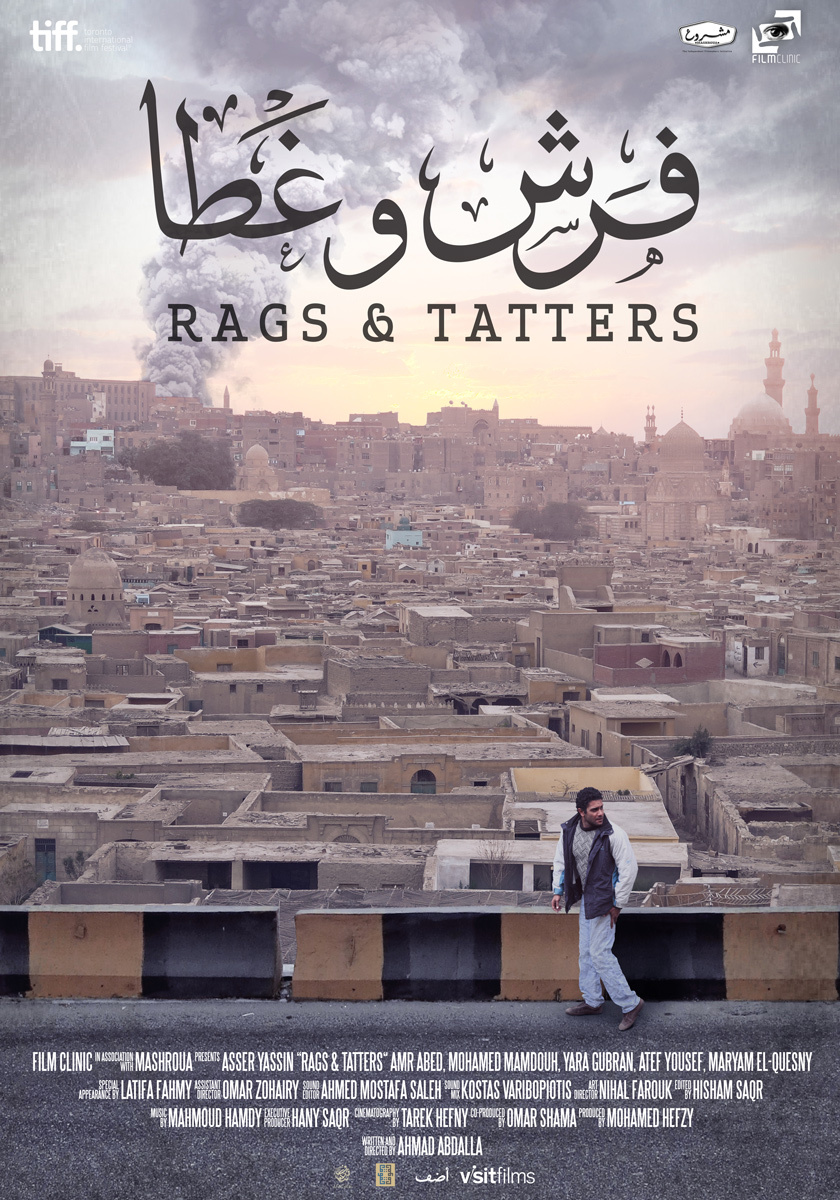

Go see "Rags and Tatters" (if you're in Cairo)

Ahmad Abdalla’s third feature film, “Rags and Tatters,” follows an unnamed convict who escapes from prison sometime during the uprising against Hosni Mubarak -- or rather is allowed to escape from prison: Some jails were allegedly opened at that time by the Ministry of Interior itself, in an attempt to foment chaos.

The man, played by Asser Yassin, is a sympathetic everyman, with dark and feeling eyes. He needs to be someone we like to look at, because his quiet, registering face is the focus of the film. As if tired of all the talk of the last two and half years -- of all the words that have been worn thin -- Abdalla has written a film with almost no dialogue. Actors’ conversations are often inaudible, no higher then a mumble. What exchanges we do hear are the most basic everyday stuff: “Cup of tea,” “God bless you.” When a young would-be revolutionary harangues his friends in the neighborhood about the need to go to Tahrir, a nearby motorcycle engine drowns out his words. The only music are some beautiful Sufi songs: unaccompanied male voices singing of holy love and yearning.

The movie is also unusual for what it shows and what it doesn’t show. It never portrays the protests in Tahrir. Instead, it is set in the streets and homes of Cairo’s poor neighborhoods. It does something radical simply by focusing closely on these environments of extreme deprivation, on their crumbling staircases and bare rooms, broken windows and peeling paint. A man’s whole life here fits in a duffle bag: a few old ID cards, some tools, a windbreaker.

Abdalla’s “Heliopolis” was a study of stasis, a day in the life of characters who go nowhere: a police conscript stranded in his guard post; and engaged couple stuck in traffic; a young man who dreams idly of emigrating. His follow-up, “Microphone,” which focused on the underground music scene in Alexandria, was seemingly quite different, full of kinetic energy. But all the eager young voices in the film still faced the stagnation and repression of Mubarak’s Egypt, and couldn't figure out how to make themselves heard.

This movie is Abdalla’s darkest and most powerful. It shares with his previous work a penchant for naturalistic acting; an under-stated social and political engagement; and an ambitious, creatively uncompromising vision.

This movie is like an inoculation against official propaganda and romanticization of the January 25 uprising. In the Q&A after the film Abdalla corrected someone who introduced “Rags and Tatters” as a “revolutionary” film. “This film isn’t about the revolution,” he said. “It’s about the conditions we lived under, and still live under.” It will only be showing in Cairo for one week, starting today.