Morocco & its arts

A chandelier from the Qaraween mosque in FeZ, which was made from a bell taken from a christian church

In the last month I have somewhat serendipitously been exposed to a lot of Moroccan art. In my new hometown of Rabat, the country's first museum of modern and contemporary art just opened. In Paris, where I was visiting last month, there are three ongoing exhibitions dedicated to Morocco.

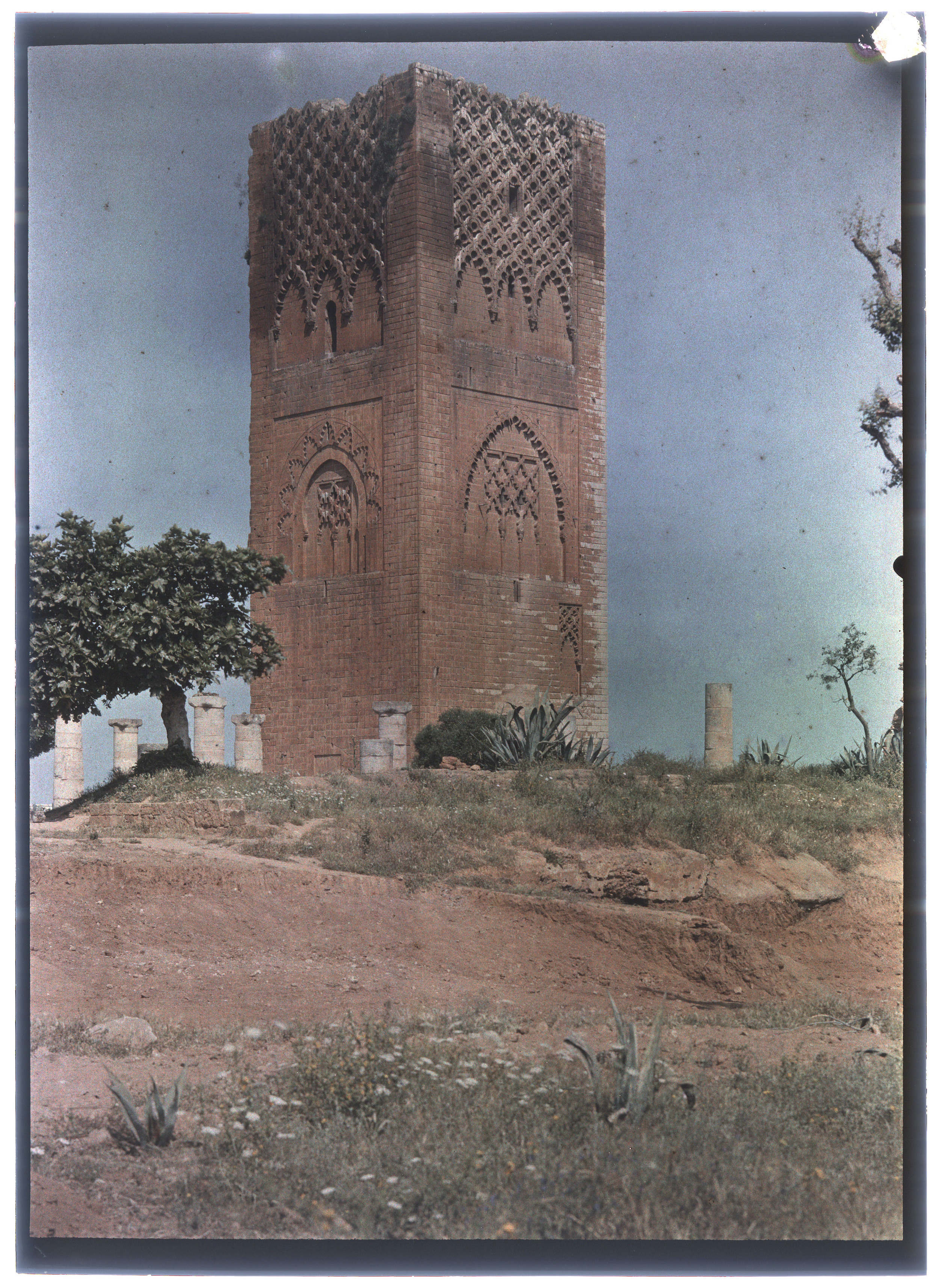

I also appreciated the way sites were illustrated with the oldest extant photographs or slides. Here is a 1937 photograph of the Tour Hassan, built centuries before as part of a monumental mosque that was never completed, in Rabat. i wish the site was still this charmingly wild.

If you can stand the line and the lobby at the Louvre, the show on medieval Morocco is well worth it, traveling through the successive dynasties that ruled Morocco (and most of Spain) from the 8th to the 15th century, founding cities such as Marrakesh, Rabat and Seville and developing arts and crafts that were imitated and prized (and stored in Church vaults) across Europe. It was the rise and fall of these Berber dynasties that inspired the Arab historian Ibn Khaldoun’s famous theories on the cyclical nature of power. The chandeliers, coins, textiles, mosaics, vases, texts, minbars and doors on display are beautiful. One does not experience their full combined aesthetic effect as one does in a mosque or madrasa, but one is able to pay them a different attention.

At the Institut du Monde Arabe, meanwhile, there is a show on contemporary Morocco and a full calendar of events. It is a little strange to open a show on contemporary Moroccan art with a film that is already 15 years old, but “Le Mur” by Faouzi Bensaidi is a gem. The short film takes place against a tightly framed white wall -- we never see beyond its edges. Bensaidi stages a whirlwind of deft vignettes: a man chases his girlfriend to a car, another throws a rock at his lover’s window, a thief clambers down, two boys get yelled at for drawing dirty pictures, a wounded man drags himself along, leaving a trail of blood. In the dark of night, workers rush to whitewash all the traces of conflict away. In the last frame, a schoolboy nonchalantly scrawls on the freshly painted wall on his way to school. It is a brilliant depiction of society as constraint and support, a barrier we hardly notice, so busy are we figuring out how to circumvent, play along and make use of it.

I also liked the black and white photographs that make up Hesham Benohoud’s “The Classroom” series, in which Moroccan school children are posed floating in various states of surreal alienation or disembodiment.

At the opening of this show, Prime Minister Francois Hollande emphasized that France and Morocco “need each other.” Relations between them are strained at the moment. Last February a French judge investigating allegations of torture called in for questioning the head of Morocco’s secret services, Abdelatif Hammouchi, who was passing through Paris. Mr. Hammouchi did not appear and Morocco suspended judicial cooperation with France. That same month, the Spanish actor Javier Bardem -- a supporter of Western Sahara’s independence -- claimed that a French ambassador had described Morocco to him as “a mistress that one sleeps with every night, that one doesn’t particularly love, but that one must stand up for.”

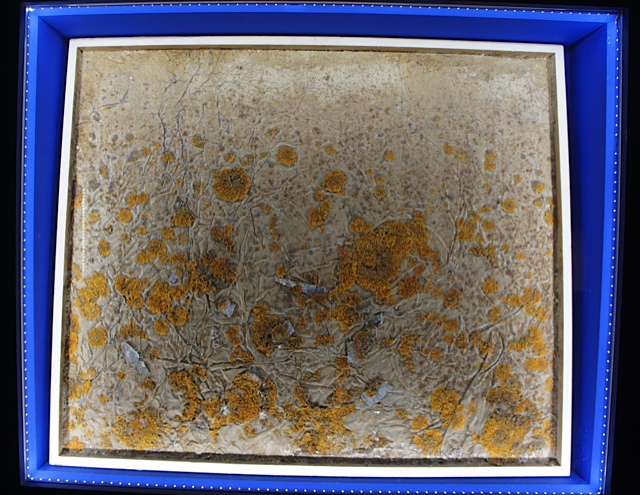

The shows in Paris have been viewed as partly an attempt to patch things up. The one at the Institut du Monde Arabe has a slap-dash quality that makes one wonder if it wasn’t thrown together, or expanded, at the last minute. It features pioneering 1960s artists of great significance such as Farid Belkahia -- who painted on animal skin, with vegetable pigments, and gave his canvases organic shapes -- and iconoclasts like El Khalil El Ghrib, who makes strange patient decaying concoctions of found materials -- stone and wood and moss and wire and fabric -- that mesmerize with the blurred traces of the creator’s intention. You can catch a glimpse of his spectacularly messy studio and hear him talk (in French) with charming earnestness about his decision not to sell his work here.

They are exhibited alongside younger artists of quite variable talent. Some of the work is great but plenty of it is immature, or heavy-handed. I thought there was a dearth of accompanying texts. Instead, staff from the Institut circulates among the crowd, repeating short memorized explanations of the pieces. The themes (Sufism, women and their bodies, religion) are rather obvious, and the show fizzles out into a strange folkloric/commercial coda, with kaftans and carpets suddenly featured at the end.

playing with the sacred

This "Glass Flower" installation at the institut du monde Arabe is best appreciated lying on one's back. The slowly pulsing lights are reflected in a mirrored dome.

The show in Paris should travel to Morocco next, and be hosted at the new Mohamed V Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. At the top of the main avenue in downtown Rabat, the two-story white building -- decorated with white mashrabeya and a silver cornice -- is architecturally subdued, more concerned with fitting in than making a statement. Inside, the building still has that slightly stage-set quality of so many cultural institutions in the region -- as if they're not quite sure who, besides the dignitaries at the opening ceremony, will show up, or if they want anyone to. No café or gift shop yet, and the shelves of the information booth are quite empty. But the staff are eager, and there were quite a few visitors on the week day I went; the museum says there have been over 30,000 since it opened.

Deconstructed teapot

What is strangest about the museum is that the visit is in reverse-chronological oder, starting with the work of contemporary young artists and ending with Mohammed Ben Ali R’bati, considered the country’s first modern painter.

R'bati was the first painter to attempt naturalistic subjects. this is a view of a procession in tangiers

This potentially interesting conceit ends up being confusing, especially as each artistic era is explained largely as a reaction to preceding historical events, artistic schools and tendencies. These includes the rejection of early Orientalist and naif art; the reaction to Western aesthetic influences and political domination; debates over building a new national art versus valorizing individual experience and expression, and pure versus expressionist abstraction, which went on for decades.

THe TWINS, chaiba tallal

ABDELKRIM GHATTAS, 1975

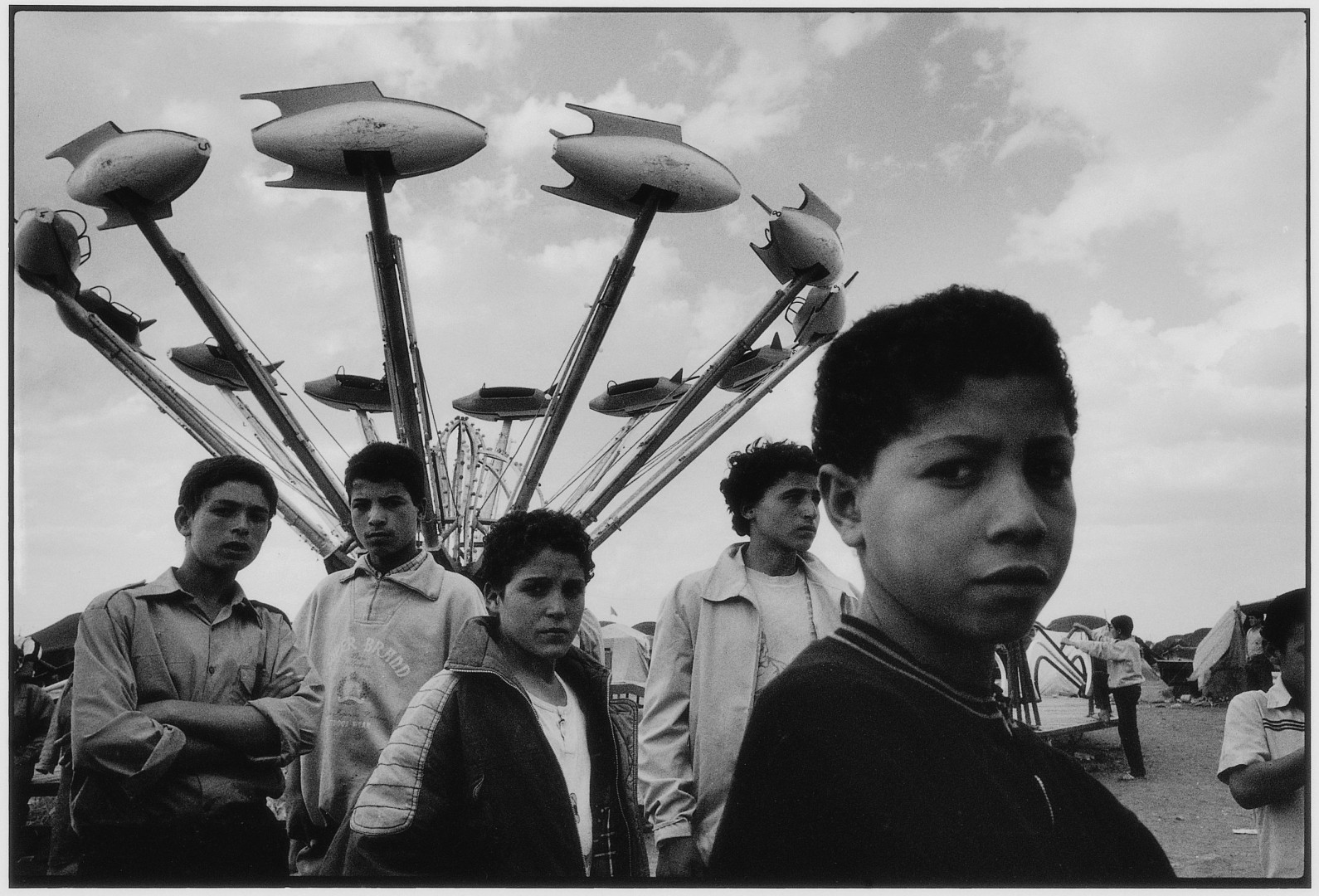

THE PHOTOGRAPHY Of DAOUD AOULAD SAID. THIS IMaGE Isn't in the museum, but many other riveting ones are

one of belkahia's iconic hands

Having only seen one room of younger artists, I thought the contemporary art was given very short shrift. But I've since discovered that a bunch of it is being housed in the basement, a choice that speaks loudly of established hierarchies (and "underground" status). Very much looking forward to going back and seeing the rest.