In Translation: Egyptian minister, the worst job in the world

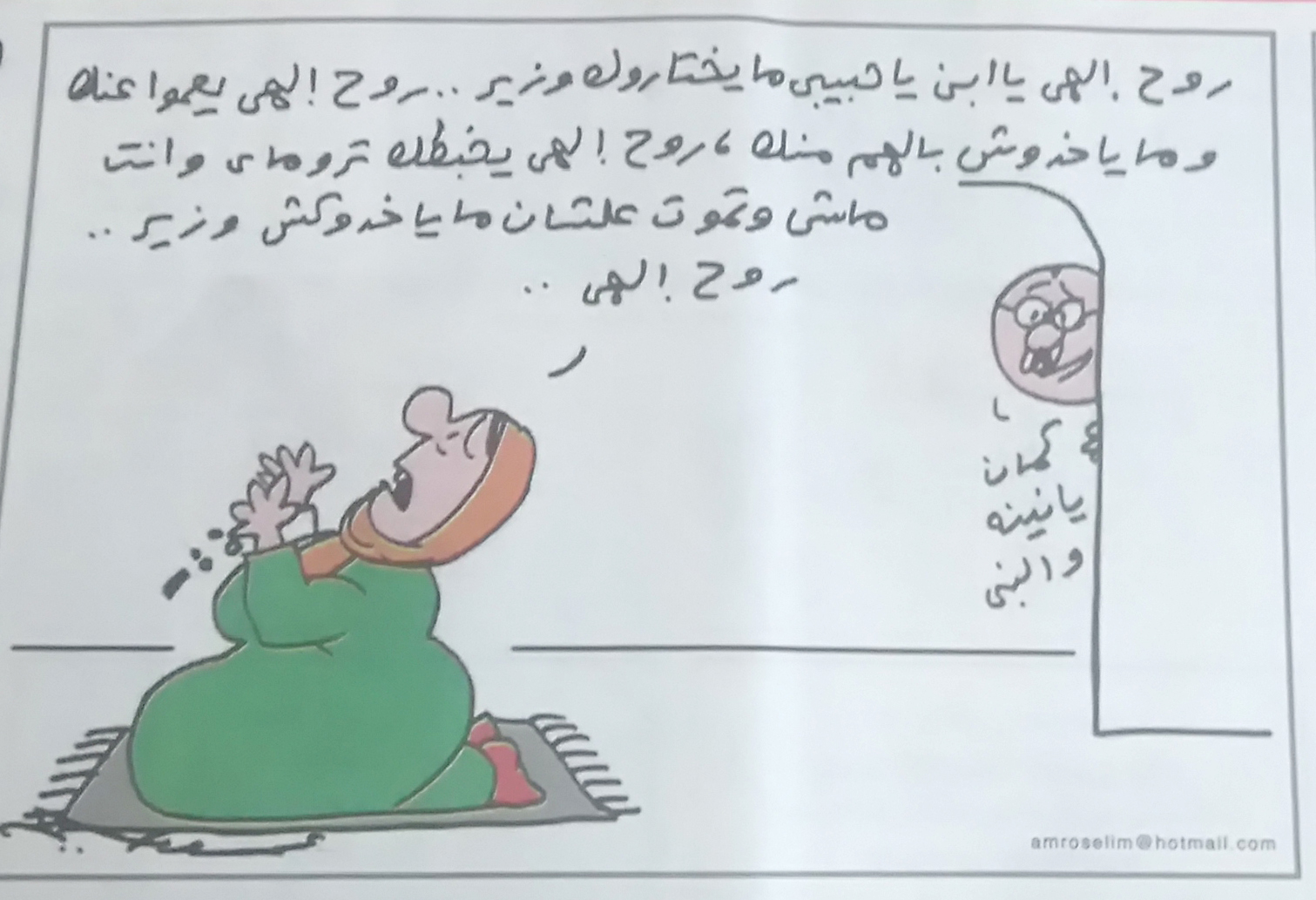

This cartoon by Amro Selim in Al-Masry Al-Youm (22 January 2017) depicts a mother praying for her son: “My son, may you be not picked as a minister. May God blind them so they do not notice you. May you die in a train accident so they would not pick you as a minister,” as her son stands in the corner saying: “Keep praying please.” Source: Mada Masr Digest.

Poor Egypt. Amidst all of the misery heaped on it in recent years — drastic curtailing of freedoms, terrorist attacks, military rule, unprecedented human rights abuses, a general descent into media vulgarity and irrelevance, grotesque injustices dished out daily, a hapless and disconnected elite, the list goes on and on –– it is in a mind-boggling economic mess. The Egyptian pound has broken all expectations after November’s devaluation and lingers at the LE18-20 to the USD level, compared to LE8.8 at the official rate a year ago and until recently never much more than LE15 on the black market. 2017 will be brutal for ordinary Egyptians of all classes, and the optimistic take that such painful austerity is a prelude to recovery leaves one wondering: where is this country headed? How will this end?

President Abdelfattah al-Sisi, when not coming up with innovative solutions to these economic challenges, faces a dilemma. Like Donald Trump, he knows he is the best man for the job of making his country great again — everyone says so on TV. But he is surrounded by incompetents and saboteurs. So yet again, for what seems like the umpteenth time since he took power in July 2013, a cabinet shuffle appears imminent. Except it’s so hard to find good help these days! For weeks, the Egyptian press has reported that prospective ministers are turning down offers to join the cabinet led by Prime Minister Ismail Sherif (whose job is reportedly safe, although probably just till the next shuffle in a few months). Amazingly in a country where it seems everyone seems to aspire to be a wazir, there are no takers.

The columnist Ashraf al-Barbary, in the piece below, has a courageous and eloquent explanation why. A little background may be necessary: under Sisi, most if not all key decisions are made in the presidency. A kind of shadow government run by intelligence officers holds the real files. And the president – as seen in the long-postponed decision to devalue the currency – waits until the very last moment to make vital decisions, wasting time, public confidence and opportunity in the process. All of this is well-known. For a writer to express himself so forthrightly in today’s Egyptian press (al-Shorouk being an upscale daily broadsheet) would have been unthinkable a year or two ago, but things are changing fast and people are fed up. The various lobbies (big business, civil society groups, political parties etc.) that would normally influence policy under the Mubarak era have no way in. Decisions are made in mysterious ways. Ministers have little leeway to implement their own vision and see no coherent plan coming from the top. No wonder Sisi’s headhunters are having trouble.

This translation is brought to you by the industrious arabists at Industry Arabic, bespoke manufacturers of fine translations. Please give them your money.

Blessed are those who turn down ministerial posts

Ashraf al-Barbary, al-Shorouk, 25 January 2017

If there is truth to the reports from government sources that many candidates have excused themselves from taking up ministerial positions, then we are right to ask the government to reveal the names of these people so that we can praise them.

Someone who would give up a ministerial post — which so many hearts long for — must be one of two types of person: a straightforward person who does not believe that he would be able to tackle the disastrous situation the country has come to due to the irrational policies that we have been following for years, and who therefore chooses to forego rather than to accept a position where he is not qualified to succeed; or a person who is sufficiently qualified to succeed but respects himself and refuses to be made into a mere “presidential secretary” who carries out instructions from above in accordance with our ancient political legacy.

Of course, the political and media militias loyal to the ruling regime will come out to heap charges of treason and of abandoning the country in a difficult time on these honorable people who have refused to take up these “high-level positions” in order to avoid certain failure, either because they do not have the qualifications and abilities to help them confront disasters they did not create, or because they know that their qualifications and abilities would not bring success amid failed policies they have no means of changing, because they have come from who-knows-where.

The opposite is entirely true: A person who refuses to play the role of extra at the ministerial level — not knowing why they brought him to the ministry or for what reasons they would remove him — is a person who deserves to be praised in comparison with a person who accepts a ministerial role while knowing that many high-level posts in his ministry and its agencies have been transformed into end-of-service benefits, which some obtain after the end of their term of service, compulsory by law, without any consideration for standards of competence and training.

The last three years have seen more than one cabinet shuffle. However, the situation has deteriorated at all levels, meaning that the problem may not be the minister or even the prime minister, but rather in the policies and ideas which are being imposed on those who accept these appointments. Accordingly, the insistence on carrying out cabinet reshuffles without any serious attempt to review the overarching policies and decisions that have led the country into economic and social catastrophe — indeed, the current policies — will not yield anything positive.

Nothing underscores the absurdity and superficiality of the cabinet shuffle and the fact that everything is coming from above more so than the status of the parliament. In theory, the new constitution gives the parties and blocs in parliament the highest word in forming the government; however, we see them waiting for whatever ingenious cabinet lineup the executive authority is so kind as to bestow upon them, just to rubber stamp it even before the lawmakers know all the names of the new ministers — as occurred when they voted to appoint the current supply minister within a few minutes.

If the authorities had the slightest degree of seriousness about reform or the desire to form a government that had the slightest degree of independence, the prime minister would have gone to the parties at the heads of large blocs in parliament for them to give him candidates from among their members for ministerial posts. This would contribute toward developing political and democratic experience on the whole, and also offer the benefit of ministers who do not owe their presence in the ministry solely to the satisfaction of a higher power, but rather to their parties, who may later seek to form an entire government, as occurs in any rational country.