Ursula Lindsey is a reporter, essayist and book reviewer who largely writes about North Africa and the Middle East, where she has lived for the last two decades. She is from California but grew up in Rome.

She lived in Cairo from 2002 to 2013 and got her start at the local independent magazine the Cairo Times. She was the culture editor of Cairo magazine in 2005-2006 and served as special projects editor at Mada Masr in 2013-2014. She was an editor of The Arabist blog.

She reported from Egypt for many years for the BBC-PRI radio program The World, and covered the Arab Spring for Newsweek, The New York Times, The New Yorker online and the London Review of Books. From 2011 to 2014, she was the Chronicle of Higher Education's Middle East correspondent.

She studied comparative literature at Stanford University, has a masters in Near East Studies from NYU (with a focus on modern Egyptian literature), and is a graduate of the Center for Arabic Studies Abroad. She speaks Arabic, French and Italian.

From 2014 to 2019, she lived in Rabat, Morocco. She was the academic director of the School for International Training’s study-abroad program in journalism there.

Today she lives in Amman, Jordan and is a contributor to The Point, and the New York Review of Books.

She co-hosts the BULAQ podcast, which focuses on Arabic literature in translation and is part of the podcast network Sowt.

Cement barrier in Tahrir Square with trompe l’oeil mural. Cairo, 2013.

ESSAYS & PUBLICATIONS

Innocence abroad, 2018. It’s remarkable, given the propensity of American officials, journalists and academics to refer to other nations and cultures as immature and underdeveloped, how frequently and consistently Americans themselves are described as children, by both foreign authors and American writers themselves.

Sisi and the press, 2014. I stumbled into journalism twelve years ago, at the dingy and convivial offices of the Cairo Times, a now defunct independent English language weekly whose Egyptian and foreign interns and journalists have gone on to report across the Middle East. I’ve worked as a reporter in Cairo ever since – as an editor at other local independent publications and as a correspondent for foreign media – and I’ve never known a worse time for journalists in Egypt than the present.

The Anti-Cairo, 2017. The regime seems to view public space as it views governance: a choice between total chaos or total control. There is no middle ground in which to negotiate interests, to discuss the distribution of resources. There is to be no politics in the city. Whatever the outcome of the plan to move the capital, it has already revealed the government’s twisted vision of the ideal city: minutely planned, shiny, ordered, self-contained, and insulated from the population. An anti-Cairo.

PUBLICATIONS

Work has appeared in the following anthologies:

With/Without: Spatial Products, Practices and Politics in the Middle East (Bidoun Inc and Moutamarat: Dubai, 2007)

The Journey to Tahrir: Revolution, Protest, and Social Change in Egypt, 1999-2011 (Verso Books, 2012).

Attacks on the Press: The New Face of Censorship, (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2017).

Arab Politics Beyond the Uprisings: Experiments in an Era of Resurgent Authoritarianism (The Century Foundation Press, 2017).

The Opening of the American Mind: Ten Years of The Point (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

LITERARY CRITICISM

Refusing Silence in Egypt, 2022. What was different this time was the way the memory of the 2011 uprising seemed not just buried but obliterated, as if it had never happened at all. Ever since it took power, the Sisi regime’s goal has been not just to undo the effects of the uprising (which Sisi has said he viewed from the beginning as “the death certificate of the Egyptian state”) but to wipe away the very story of what happened with a flood of lies and threats.

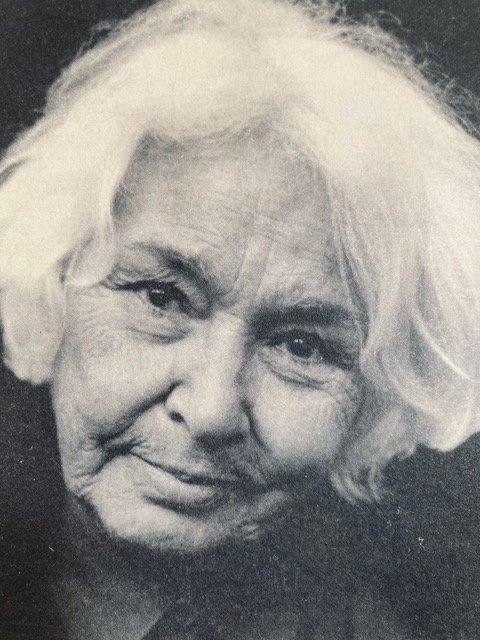

In The Fire, 2021. I interviewed El Saadawi in 2004. I was a twenty-five-year-old journalist who had read a few of her books. She was one of the best-known Arab feminists in the world but a marginalized figure in her own country—banned by the authorities from government posts and media appearances, railed at by Islamists, at odds with much of the Egyptian public because of her criticism of practices such as veiling, polygamy, unequal access to divorce and inheritance for men and women, and female genital mutilation.

Family Values, 2020. The women in Leila Slimani’s novels are unhappy. The men are dissatisfied too, but they are secondary, more oblivious characters. The women are unhappy because their husbands don’t understand them, because their children are a burden on them, and because their existence strikes them as humiliatingly humdrum.

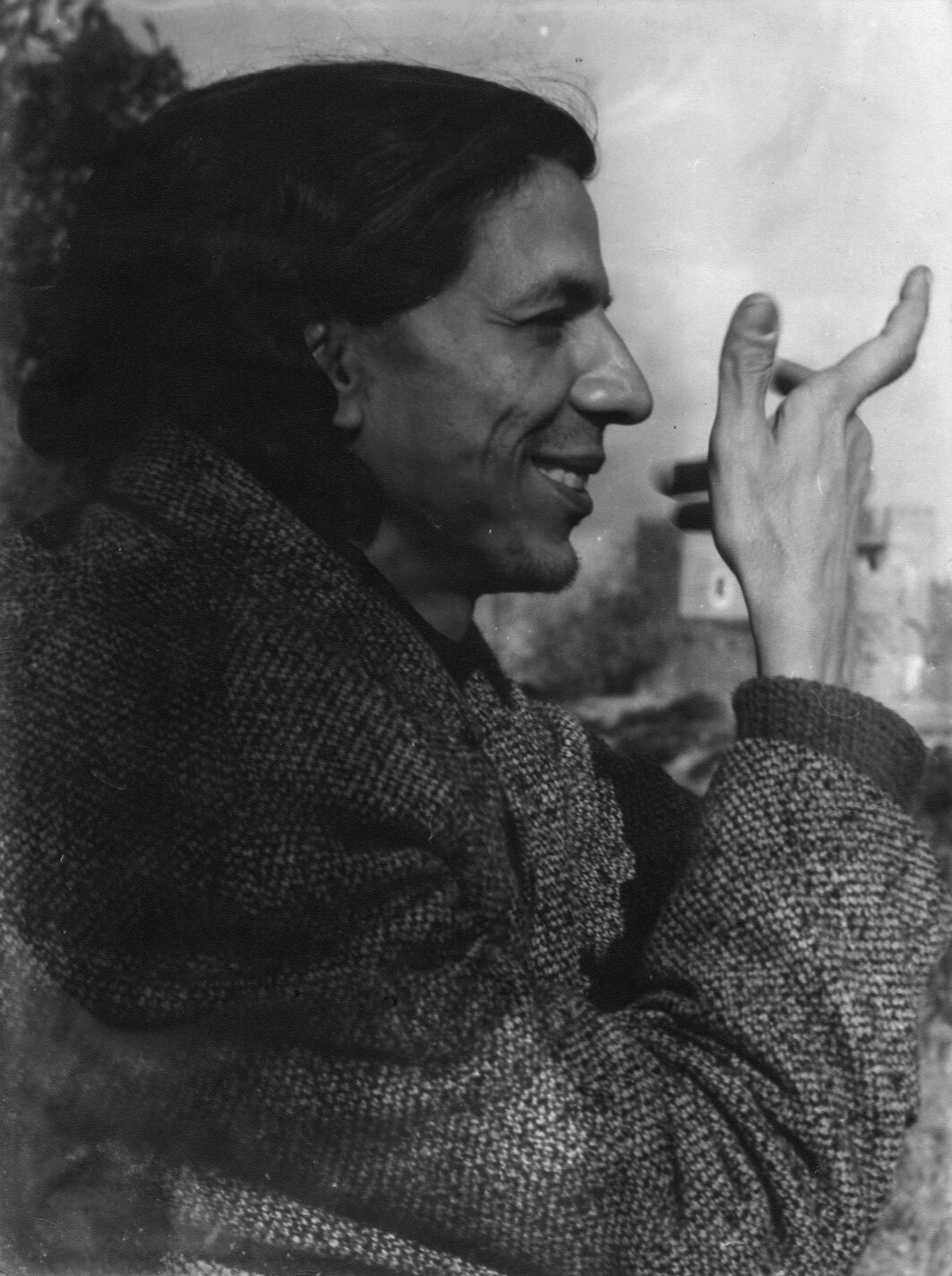

This Land is Mine, 2020. The late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008) liked to write in the mornings, preferably in a narrow room with a window overlooking a tree. He required solitude and coffee; he wrote in black ink on loose, thick, white paper. He often listened to music. His poems, he told the journalist and fellow poet Abbas Beydoun in 1995, always started out as a cadence, a tempo.

Coup de Theatre, 2019. The Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous used all the dramatic strategies at his disposal to provoke the audience to question authority. His hope seems to have been that spectators would join in the discussion onstage, take over the theater, and be inspired to other forms of revolt. That no such thing happened left him terribly disappointed.

Lessons of Defeat, 2019. Arwa Salih’s aim is to snatch, from the wreckage of her generation’s hopes and illusions, some useful knowledge to be shared with those who come after her: “I find it strange that we should squander our insights into this history just because we ourselves were defeated with such humiliating ease.”

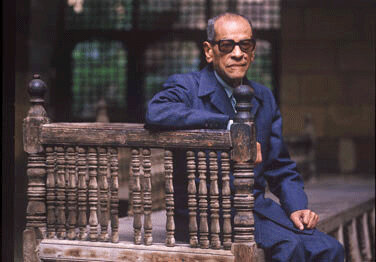

Naguib Mahfouz’s World, 2018. I met Naguib Mahfouz once. It was in the winter of 2006, and I’d been living in Cairo for three and a half years. […] The hotel faced the Nile across four lanes of traffic. There was a metal detector at the front door. Ever since he was nearly killed by a young fundamentalist in 1994, Mahfouz no longer frequented the downtown cafés where he had met friends and fellow writers for half a century.

Restoring Morocco’s Past, 2018. Ahmed Bouanani, who died in 2011, was a prolific artist whose work was constantly censored, stifled, sidelined, ignored, or damaged, by men and sometimes by natural catastrophe.

REPORTING

Ancient Egypt for the Egyptians, 2021. The subtitle of Wilkinson’s book is “The Golden Age of Egyptology.” This he identifies as the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the study of ancient Egypt acquired its scientific underpinnings and the most famous discoveries were made; it was also when countless antiquities were transferred from Egypt to private collections and European museums, and Egyptians themselves were largely excluded from the study of their past.

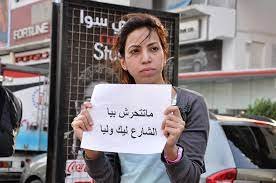

Me Too in Egypt and Morocco, 2021. On July 1, 2020, Nadeen Ashraf, a twenty-two-year-old student at the American University of Cairo, noticed that a 2018 post by a fellow student to an unofficial university-related Facebook group had been removed. The post had warned about another student, Ahmed Bassam Zaki, a young man from a rich and powerful family who sexually harassed and blackmailed young women, and it had garnered many comments, including by other female students who corroborated its allegations.

Jordan’s Endless Transition, 2020. In Jordan, unemployment is high, teachers are protesting, and water is running out.

Who Gets Arrested (In Morocco) For Having an Abortion? 2020. On the arrest of journalist Hajar El Raissouni.

The Lebanese Street Asks: Which is Stronger, Sect or Hunger? 2019. On the protests in Lebanon against corruption and sectarian governance.

Is Tunisia Ready for Gender Equality? 2019. The political unrest and economic crisis I found in Tunisia seemed to overshadow the subject I had come to report on: a proposal to make Tunisia the first Arab country in which inheritances would be divided equally among male and female relatives.

Can Muslim Feminism Find a Third Way? 2018. Moroccan scholar Asma Lamrabet argues for a progressive, contextual reading of the Quran. She doesn’t claim, as Islamists do, that Islam already gives women all their rights. She argues that it could, if it was stripped of centuries of misogynist interpretation by male scholars.

Lesser Evils, 2017. On the French presidential election, the far-right and the rise of Macron, viewed from Marseilles.

Why So Much Cruelty? 2017. Tunisia’s Truth and Dignity Commission is unique in the Arab world. But is the country too small a place to tell the truth about human-rights abuses?

Cairo, A Museum of Ghosts, 2016. Egypt’s writers and artists largely supported the military coup. Now they have less freedom than ever.