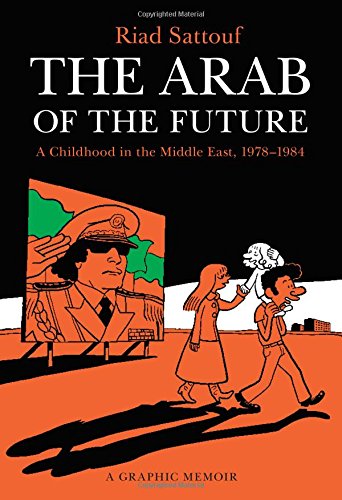

I've just published a review in The Nation of the first two volumes of French-Syrian cartoonist Riad Sattouf's The Arab of the Future (volume 1 is out in English). Sattouf grew up in Ghaddafi's Libya and above all in Hafez Al Assad's Syria and has penned a disturbing, affecting and darkly funny childhood memoir.

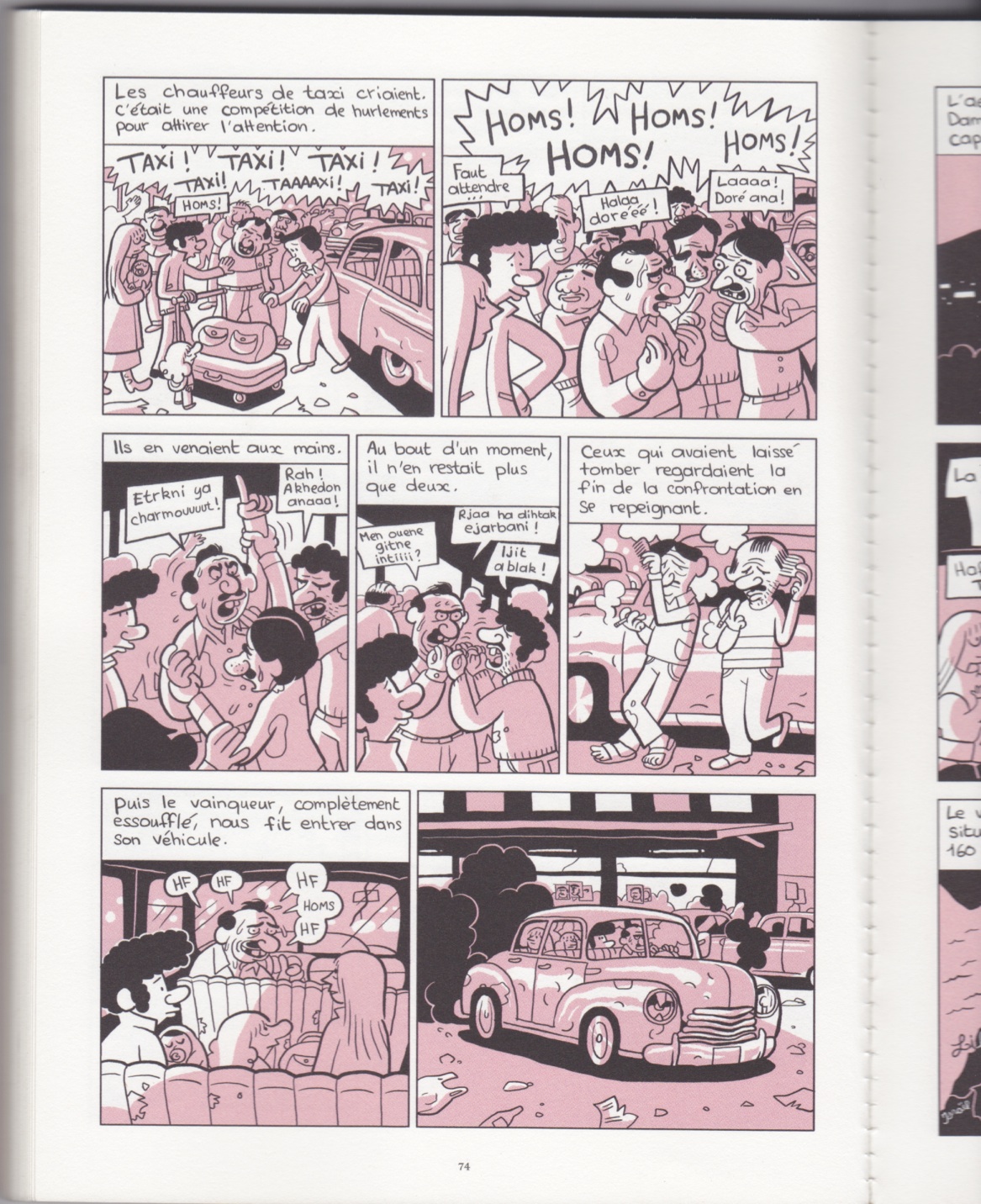

It’s 1983, and a family has landed at the Damascus airport. The father, who has avoided military service, bribes his way into the country. Accompanying him are his foreign wife and small blond son. Outside the airport, Syria assails them. A scrum of screaming cab drivers fights over the startled new arrivals. Cabbies abandon the brawl and compose themselves on the sidelines, combing their hair and smoking cigarettes, until the last one left shouting—and close to keeling over from his exertions—hustles the family into his taxi. He ashes his cigarettes through the moving vehicle’s missing floorboard.

This scene of homecoming and culture shock falls about halfway through the first volume of The Arab of the Future, a graphic memoir by the French-Syrian cartoonist Riad Sattouf. The book delivers a vision of childhood that is both extreme and familiar: its terrors and painful revelations, the utter mystery and absolute power of adults, the sensory details that lodge forever in the memory. But Sattouf’s vision is also of the unusual childhood he lived in Moammar El-Gadhafi’s Libya and Hafez al-Assad’s Syria, as well as in the shadow of his father and his delusions. The Arab of the Future blends a rueful backward glance at the early days of two dictatorships that finally imploded in the Arab Spring and an intimate indictment of the way boys were taught to be men.

Sattouf, who is 37 and lives in Paris, has directed two movies and written dozens of graphic novels, many of them focused on adolescence and sexual losers (one is called Virgin’s Manual, another No Sex in New York). Other work is drawn from life: For one piece, he spent 15 days in an elite French high school. Between 2004 and 2014, Sattouf contributed a weekly comic called “The Secret Life of Youth” to the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. Based on scraps of life seen and heard on the streets and subways, it was preoccupied, like much of Sattouf’s work, with observing those moments of cruelty, violence, or strangeness that happen in plain sight but are generally passed over in silence, purposely ignored.