My friend Mohammed Si’ali, a veteran reporter for the Spanish news agency EFE and other outlets in Cairo and elsewhere in the region, has written an interesting piece on the evolution of al-Qaeda’s strategy in response to the Arab uprisings since 2011. Piecing together its reaction to the 2011 protests, the secession of the Islamic State from its ranks in 2013, the rebranding of the Nusra Front in 2016 and the emergence of a new united front of Sahelian jihadist groups in 2017 – among other things – he sets out a vision whereby al-Qaeda is trying to mainstream, win the support of Islamists disappointed by the Arab Spring, and combine a global strategic vision oriented against the West with pragmatism at the local level. To borrow from the HSBC ad from a few years ago, al-Qaeda appears to be trying to be glocal organisation. As ISIS faces military setbacks across the region, this has important consequences for the future of jihadism.

This In Translation feature is made possible with the support of our friends at Industry Arabic, a “Katiba Hans Wehr” of Arabic-English translation. Please give them your business!

Evolving with the Arab Spring: Is al-Qaeda Striving to Transform into a “National Liberation Movement”?

Mohammed Si’ali, Center for Kurdish Studies, 5 April 2017

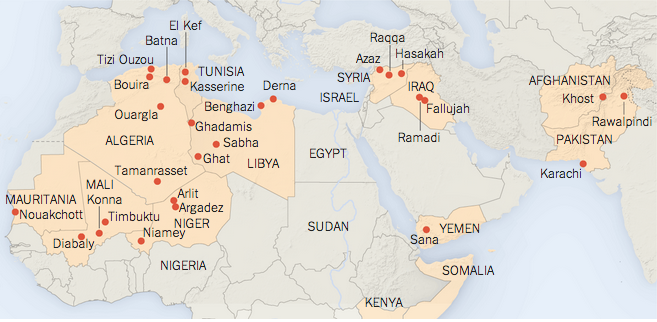

Abstract: The new alliance announced last month between three jihadist organizations in Mali under the banner of al-Qaeda and local jihadist leadership, as well the contents of its founding declaration, have raised questions about its rapid efforts in this region to evolve ideologically and organizationally with the new reality that has characterized the popular uprisings in the MENA region since 2011. With the goal of improving its survival, development, and practical abilities in light of these new conditions, al-Qaeda is accomplishing this by reducing armed, violent acts and participating in peaceful political action and soft influence. Consequently, what has appeared is something that resembles an “Islamic national liberation movement,” whether in the MENA region or other places where this organization exists, such as the Greater African Sahara.

§§§

At the outset of the “Arab Spring,” al-Qaeda dreamt that it would finally obtain a popular ally and become the equivalent of the military wing of the popular Islamist movement. Its goal of establishing a caliphate in the Islamic world and liberating it from external influence seemed an imminent reality. The Arab uprisings coincided with the killing of Osama bin Laden on 2 May 2011 in an operation by American special forces in Pakistan and Ayman al-Zawahiri’s emergence as al-Qaeda’s leader. After the Arab uprisings, which overthrew dictatorial secular governments in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Yemen, al-Zawahiri issued a political manifesto in August 2012 to specify Islamic jihad’s role in this stage. He emphasized the necessity of “aiding Muslim people in their revolutions against corrupt tyrants, and enlightening them of the necessity of Sharia rule.” He also broadly called for “working towards the establishment of a Caliphate that does not recognize nation-states, links to nationalism, nor the borders imposed by the occupiers.” In September of the same year, he broadcast a military manifesto placing limits on armed action that member groups practiced under the banner of al-Qaeda. It focused the fighting on the United States and aimed to reduce military operations inside Islamic countries, thereby preventing those societies from eschewing jihad. Additionally, he showed many film clips that described the course and direction of the revolutions to steer their uprisings toward Sharia law, ending with the establishment of a caliphate state.

Al-Zawahiri’s interest in the direction of the Arab Spring shows that he, along with others in al-Qaeda’s leadership, sees these revolutions as complementary to the jihad carried out by the different arms of the organization and as a result of the 11 September 2001 attacks on America. As such, these attacks had pushed Washington to breathe life into popular pressure in Muslim countries, which “blew up in the faces of its clients,” i.e. the local governments. Additionally, Adam Yahiye Gadahn – the American citizen who worked as a senior spokesperson for al-Qaeda and was killed in an American drone strike in Pakistan in early 2015 – saw that the jihadist attacks against American interests and its allies had “eliminated many of the material, moral, and psychological obstacles that used to prevent the Ummah (Islamic community) from liberating itself from the corrupt and despotic governments subordinate to the West.” He added that youthful opposition in countries with popular uprisings had learned from the jihadists’ experience in their call for toppling tyrannical regimes on the internet, as well as the fatwas from jihadist scholars to remove despotic governments for their lack of Sharia law, which had a prominent role in liberating the hearts and minds of Muslim youths.

On this basis, al-Zawahiri considered the success of the revolutions as a victory for al-Qaeda over the West, since the revolting peoples “want Islam and Islamic rule, while America and West fight it.” Similarly, in one of his lectures he showed bearded demonstrators in Egypt carrying al-Qaeda flags and shouting slogans in defense of the religious state against the secular state. In another of Gadhan’s tapes, a group of demonstrators was shown praying at one of the sit-in sites, with women wearing niqabs taking care of an injured person and a man pointing to the Quran. Al-Zawahiri added in a 2011 recording:

“The pro-American media claims that al-Qaeda’s method of clashing with regimes has failed. This same media pretends to ignore that al-Qaeda and most jihadist currents have struggled for more than a decade and a half mostly by abandoning the clash with regimes and focusing on striking the head of the global criminals (the United States). Thus, this method, especially after the September 11 attacks, has led, through orders from America, to the regimes’ loosening their grip over their people and opponents, which helped the movement and culminated into an eruption of massive public anger. This confirms what Osama bin Laden, may God have mercy on him, used to emphasize, that we increased pressure on the idiots of the modern era, America, which will lead to its weakening and the weakening of its clients. So, who are the real winners and losers of this policy?”

Al-Qaeda did not only attribute to itself the outbreak of the Arab Spring, but also considered the leadership of various jihadist currents, such as in Egypt, as precursors to the massive uprisings against the current regimes and those that have existed since the late 1970s. In this regard, al-Zawahiri said in one of his messages to the Egyptian people after the revolution of January 25, 2011:

“God knows that I always hoped to be in the front line of the Ummah’s uprising against injustice and oppressors. Before my emigration from Egypt, I had been eager to participate in the popular protests of 1968 against the setback represented by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s government. Then, I participated in several demonstrations and protests against Sadat and his administration. I was with the protesters in Tahrir Square in 1971, whom I considered dear brothers. It was for them that the great events of the latest Egyptian revolution against Hosni Mubarak and his corrupt government occurred. If not for fear of what danger would befall them, then I would mention them by name and praise their brave deeds. Likewise, I have repeatedly called, in my words to the Arab people and the Egyptian people specifically, to rise up against the regimes of corruption and tyranny that have dominated us.”

Despite al-Qaeda’s new, strengthened approach after 2011, in 2008 al-Zawahiri had called for action in addition to the struggle and propaganda. He called for demonstrations to change the “corrupt reality” and establishing an Islamic state, while modifying the pursuit of these goals through the tactic of “fixed elections.” Thus, after the workers’ demonstrations on 6 April of the same year in Mahalla el Kubra near Cairo, he said:

“The workers and students must move their anger into the streets. They must turn the mosques, factories, universities, institutes, and high schools into centers of jihad and resistance. Everyone must mobilize, because it is not just one group or organization’s battle, but the entire Ummah’s battle. The Ummah must stand shoulder to shoulder with its fighters, its men, its women, and its masses to expel the crusading invaders and Jews from the lands of Islam and to establish an Islamic state.”

Since the outset of the Arab Spring, al-Qaeda began employing concepts that were unfamiliar in the jihadist lexicon, such as “revolutionaries,” “revolution,” and “resistance,” alongside religious concepts. This turning point in the direction of al-Zawahiri’s propaganda was reinforced in one of his recordings to businessmen. In it, he said that they should “benefit from the recent opening in Tunisia and Egypt” and establish new media outlets to call for “the true creed of Islam, which is liberated from its dependence on the arrogant and rejects the injustice of corrupting rulers.” He added, “The noble free people who care about Islam in Tunisia must wage a propagandistic, provocative, and popular campaign to gather the Ummah. They must not stop until Sharia is the source of law and order in Tunisia.” These ambitions did not appear out of thin air. During the Arab revolutions, it was the young and old of the jihadist currents, despite their small numbers, who took their place among the poplar demonstrations, wearing Afghani garb and raising the black flags of al-Qaeda. In Tahrir Square, Egypt during the period following the 25 January Revolution, pictures of Osama bin Laden were sold alongside pictures of deceased Egyptian leaders Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat.

It was clear after the revolutions of the Arab Spring that al-Qaeda strove to profit from a popular ally in those countries and to participate in peaceful movements, but without slackening its violent activities. In the document “The Victory of Islam,” al-Zawahiri called on the Islamic currents to “aid Muslim people in their revolutions against tyrants and to enlighten them of the necessity of Sharia rule.” In the document “General Directives for Jihad,” the leader of al-Qaeda required that military action be focused against the United States. More importantly, they demanded that the jihad avoid harming Muslims and religious/ethnic minorities during acts of violence so that they are not roused against the jihadists. He also called for peace with local regimes to proselytize, recruit, and gather funds. As for the places that fell under jihadist control, he demanded that “wisdom prevail,” meaning to prioritize propaganda and education to avoid the jihadists’ expulsion from those regions due to civil discord or revolt by those opposed to their occupation.

According to al-Qaeda, the conflict between the people and regimes is the local manifestation of an original conflict between the former and the West. In its view, the regimes in Muslim countries are a façade or tool that the West has used to rule the region remotely since the beginning of what Adam Yahiya Gadhan called the “age of neo-colonialism.” But in spite of the outset of the confrontation between al-Qaeda, supported by its allies, and the Syrian and Iraqi governments, as well as its continuing operations in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, Algeria, Mali, Yemen, etc., the original tactic of this organization has been to avoid conflict with regimes in Muslim countries, except where confrontation is necessary.

One Moroccan member of the “Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham” (formerly the al-Nusra Front, considered the formal arm of al-Qaeda in Syria) says that al-Qaeda “is trying to exploit the situation that emerged from the Arab Spring to penetrate Islamic society. It also strives, if possible, to avoid direct clashes by instead working tactically, except in places where there is fighting already.” It is confirmed that al-Zawahiri’s intensive speeches during and after the Arab revolutions were directed at revolutionaries and moderate Islamic currents. The organization itself is managed internally by secret decisions issued by Shura councils, the general leadership council, and orders from the general commander, not through open statements.

Despite the new direction of al-Qaeda’s leader and all its affiliated factions, the “Islamic State” opposed it and unleashed its own military actions against Shiite citizens, especially in Iraq and Syria, where it carries out daily car bombings in restaurants, public markets, hussainiyas (Shia congregation halls), and pilgrimage caravans. This lack of obedience pushed the general leadership of al-Qaeda to wash its hands of the Islamic State through a formal statement on 22 January 2014. It stated its eagerness for the different jihadist organizations “to be part of the Ummah, and to not take guardianship over its rights, nor dominate it, nor deprive it of its right to choose who rules it from among those who fulfill the conditions of legitimacy.” In addition to its defiance of the directives of al-Qaeda’s leadership, the Islamic State carries out attacks against other jihadist organizations that had publicly or implicitly adopted al-Qaeda’s new direction, such as the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in Syria.

The point of departure in the dispute between al-Qaeda and the Islamic State was the latter’s refusal to comply with al-Zawahiri’s request to restrict its military operations in Iraq and to leave the jihad in Syria to the former al-Nusra Front (before it changed its name and joined with al-Qaeda). The Islamic State did so because it considered the Levant to be a separate geopolitical province wherein it leads most of the Syrian jihadists; as such, the Islamic State believes that it better understands their society.

The Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s experience was repeated in Mali, where branches of Ansar Dine, which include the Macina Liberation Front, al-Mourabitoun, and the Saharan leadership al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, announced at the beginning of this month (April 2017) an alliance under one organization calling itself the Jama'a Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin. After renewing their allegiance to al-Zawahiri, they specified their main goal as “standing as the first line of defense against the occupying crusading enemy.” Just as in the founding statement of the new organization, led by the Malian al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadist Iyad Ag Ghaly, it cited the foundations of al-Qaeda’s jihad, which include “good will towards people, becoming familiar with them, engaging their hearts and minds, and not burdening them with anything they cannot bear.”

Conclusion: While the Islamic State aims to apply its international, truly extremist vision, a vision in which some leaders of al-Qaeda used to believe, the strategy changed completely when the latter began to decentralize its global organizational structure and establish regional movement branches in Muslim countries. According to this strategy, local jihadi leaders direct its operation while enjoying tribal, religious and ethnic legitimacy. In this way, it can make broad social alliances and separately adapt its operations according to local circumstances in each country. The issues that matter include people participating in government, supporting Muslim minorities, and fighting against external influence. Thus, al-Qaeda has added a temporary tactical dimension that loosely joins the organization’s general leadership and its strategic goals on one hand with the local issues of Islamic societies and its short/long-term goals on the other hand. The point of this new direction is to eliminate the barriers between moderate and radical Islam and to make the organization appear like a “national Islamic liberation movement.” It could also become alluring to youth groups inside Islamic political movements, if they are exposed to unexpected tyrannical treatment typical of the political rat race, continual economic injustice, repressive governmental practices of in Islamic countries, or if some of them continue to depend on the world’s superpowers. This may prove to be the case, especially given the rarity and weakness of modern opposition fronts and the growing attempts by the superpowers’ client states at brutal, vertical control.

As a Moroccan journalist and researcher based in Rabat, Si’ali worked as a correspondent for a global news agency as part of its bureau for the Middle East and Gulf regions between 2011 and 2016. Subsequently, he has reported on the development of Islamic extremists in the region and throughout the world. He earned a BA in Public Law and Political Science from the University of Tangier, Morocco.