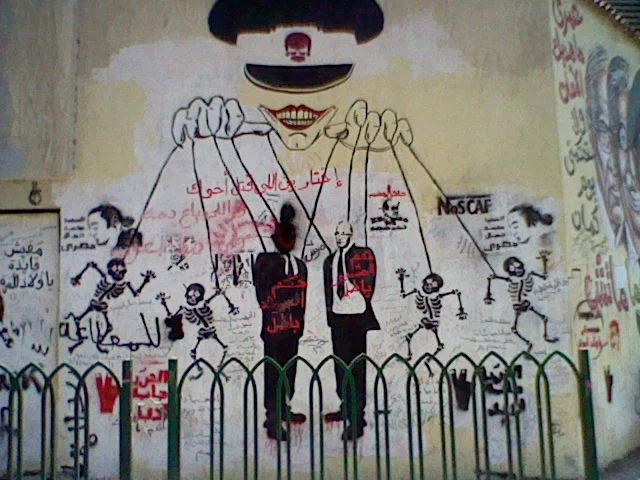

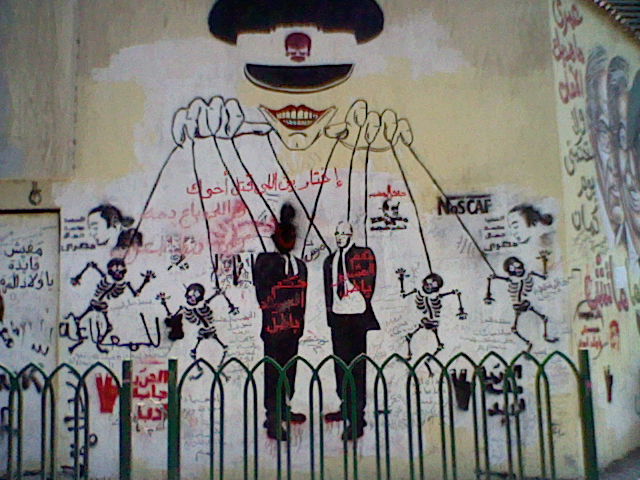

Photo of graffiti in Tahrir Square by Bilal Ahmed

This guest post is written by Bilal Ahmed, a writer and activists who is preparing for graduate research that compares the tribal laws and central governance of the tribal areas of Pakistan, and Yemen.

During their brief tenure in power, the Muslim Brotherhood and Mohammad Morsi were increasingly accused of fascism. Now, as Egypt’s crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood continues, the accusations of fascism have begun again. Much of this is because popular discourse has a knee-jerk tendency to link any form of authoritarianism with Nazi Germany. It becomes easier to do that in a national context in which we see fierce nationalism, growing xenophobia, assault against domestic minorities, and the gleeful celebration of state violence.

Let us be clear: Egypt hasn’t gone fascist. And saying that constrains how we should think about its politics in the coming years.

When we compare trends in Egyptian politics to something as complicated as the rise of Continental European fascism, we are as much probing the idea of Egypt going fascist as we are the nature of fascism itself. The rise of fascism in Europe was the result of specific political factors that, although currently present in Egypt, have not been rallied in the service of mass politics in a way that invites the word.

It is far more accurate to compare events in Egypt with the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1848 that established the Second Republic. That revolution came as the result of a wave of spontaneous revolts in 1848 that were very similar to the Arab spring. Similar to Egypt now, the initial overthrow of Louis-Philippe led to the decline of the parliamentary experiment that succeeded him, which was co-opted by a series of increasingly conservative leaders in favour of the status-quo. Eventually, the struggle ended with the rise of Napoleon III, who became both France’s first president and its last monarch (he styled himself as a Prince-President.)

Napoleon III had won the presidency in December 1848 and was hailed even initially as a candidate who, although not desirable, would be sufficient to end a variety of domestic issues. These included national unrest, economic instability, and prevent a revolutionary push by other forces, then mainly proto-communist factions. Sound familiar? He eventually came to be France’s absolute ruler as the result of a political stalemate over restrictions on universal suffrage which gave him the opportunity to present himself as the answer to an exhausted desire for national order. The National Assembly of the Second Republic had stagnated so greatly that it was reviled by the populace that established it only a few years earlier. Napoleon III then seized the opportunity to launch a coup d’état on 2 December 1851 that was approved in a later referendum, and which heralded a new era of strongman rule with democratic pretenses.

Of course, we should be wary about comparisons between Napoleon III and Egypt’s commander of the armed forces, Abdel–Fattah El-Sisi. Sisi’s rule has just begun, for one, and the complexities of both situations could have led to any number of leaders breaking through. (Including the unlikely possibility of Morsi himself). The point to focus on here is that of short-lived democratic experiments, which begin with popular dissent, and are then curtailed with widespread approval of a paradoxically equal scale (or greater as was the case with the tens of millions of Egyptians who marched against Morsi.) Their quick collapses are usually due to some political maneuvering, whether through Napoleon III’s well-timed defense of universal suffrage, or Sisi’s equally well-timed coup after mass demonstrations, followed by an insistence that a war on terrorism is taking place. It is not fascism. It is smart counterrevolution.

Once we accept that what we are seeing isn’t so much fascism as it is a pushback against democracy-minded upheaval, then we can begin to have honest discussions about fascism in an Egyptian context. Fascism hasn’t taken hold of Egypt’s state institutions, which are instead being held by cynical elites who are circulating whatever mythology will direct the public away from demanding structural change. Still, the seeds of fascism are everywhere.

Much of this is less “Egyptian” than it is a direct consequence of market-driven societies. There is a great deal of scholarship on how numerous features of consumerism, such as advertising, popular entertainment, and market surveillance, inadvertently helps foster conditions where the public more easily acquiesces to fascist authoritarianism. These phenomena have Egyptian manifestations in the same way as do the effects of economic scarcity in making politics more provincial. This is mainly because intense conditions of austerity tend to force a reliance on more ancestral ties of religion and ethnicity, especially when violence occurs.

The conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, and a general sense of powerlessness that followed World War I, drove the classical fascist movements. We mostly remember the racial aspects of these mobilizations, but fascists were diverse in the mythologies they used to create a cult of power, from homophobia to labor politics. They key is that the cult of power opposed itself on those designated as nationally “weak” and in need of being violent expunged. These drives allowed fascists to flee their own mortal vulnerabilities in a period of prolonged crisis and to embrace totalitarianism.

But elites didn’t so much subscribe to these philosophies as they did circulate them as an unwieldy attempt to preserve their own power. This was particularly true with anti-Semitism. Fascism happened in part because this circulation blew up in everyone’s face. The myths took on a life of their own and eventually drove a nihilistic revolutionary push. This crucial step isn’t observable in modern Egypt.

And yet, I think it is actually not unwarranted to see an intimation of fascism in people cheering for the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The current worship of SCAF is directly related to a feeling of national weakness. The Egyptian military becomes poetically seen as everything that Egypt should be: strong, prosperous, and willing to defend national values (never mind its actual capabilities, and the fact that it has essentially degraded into an economic empire for its senior leaders.) We are certainly seeing the possible future of something terrifying.

But it remains that: a possibility. The main problem I have with calling Egypt fascist is its tinge of historically-blind pessimism. After all, revolutionaries quickly re-grouped in France, and seized an opportunity provided to them by the Franco-Prussian War to establish a number of communes, most notably in Paris itself. And there was another wave of revolutions that began in 1917 with the Russian Revolutions. The eventual, temporary victory of fascism in much of the continent took place after fierce combat with anti-fascists who had a very different idea of the world that would succeed the decaying European political order.

It is too soon to say how these possibilities, whether of a future revolution against the Egyptian military, or the eventual emergence of fascist authoritarianism by a nihilistic revolutionary faction, will play out. However, one thing seems clear: the coming months, and years, will be crucial in determining whether or not fascism is really coming to Egypt. For now, let’s all use caution in dropping the analytical f-bomb.