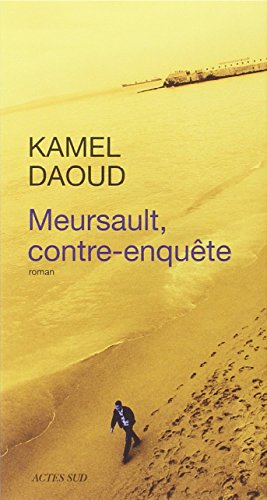

The Algerian writer Kamel Daoud's Meursault, contre-enquete is one of the best books I've read in a while. Inspired by Camus' The Stranger, it is a brilliantly written, sharp, sad, angry look at colonialism, religion, and the limits of "liberation." It is narrated by the brother of the unnamed Arab killed and quickly forgotten in Camus' novel. Adam Shatz has a great profile of Daoud, the city of Oran, where he lives, and the Algerian literary scene in the New York Times magazine.

After college, Daoud took a job as a crime reporter for a monthly tabloid called Detective. (“What made ‘The Wire’ so great,” he told me, “is that it’s a collaboration between a writer and a policeman, the dogs of the world.”) It was through traveling to small, remote towns, where he wrote about murder trials and sex crimes, that Daoud discovered what he calls “the real Algeria.” When Detective folded in 1996, he went to work for Le Quotidien d’Oran. While other journalists complained of the danger they faced from Islamist rebels, Daoud rented a donkey and went out to interview them. He reported on some of the worst massacres of the civil war, including the 1998 killings in the village of Had Chekala, where more than 800 people were slaughtered. His work as a reporter, Daoud told me, left him suspicious of “hardened positions and grand analyses,” and that sensibility infused the column he began writing for Le Quotidien. Daoud upheld no ideology, spoke in no one’s name but his own. To his new admirers, this was something to celebrate: the emergence of an authentically Algerian free spirit. To his adversaries, Daoud became the face of an Algerian Me-Generation: selfish, hollow, un-Algerian.

The New Yorker has also just published a short interview with Daoud and more importantly an excerpt from the forthcoming translation of his novel.

Musa was my older brother. His head seemed to strike the clouds. He was quite tall, yes, and his body was thin and knotty from hunger and the strength that comes from anger. He had an angular face, big hands that protected me, and hard eyes, because our ancestors had lost their land. But when I think about it I believe that he already loved us then the way the dead do, with no useless words and a look in his eyes that came from the hereafter. I have only a few pictures of him in my head, but I want to describe them to you carefully. For example, the day he came home early from the neighborhood market, or maybe from the port, where he worked as a handyman and a porter, toting, dragging, lifting, sweating. Anyway, that day he came upon me while I was playing with an old tire, and he put me on his shoulders and told me to hold on to his ears, as if his head were a steering wheel. I remember the joy I felt as he rolled the tire along and made a sound like a motor. His smell comes back to me, too, a persistent mingling of rotten vegetables, sweat, and breath. Another picture in my memory is from the day of Eid one year. Musa had given me a hiding the day before for some stupid thing I’d done, and now we were both embarrassed. It was a day of forgiveness and he was supposed to kiss me, but I didn’t want him to lose face and lower himself by apologizing to me, not even in God’s name. I also remember his gift for immobility, the way he could stand stock still on the threshold of our house, facing the neighbors’ wall, holding a cigarette and the cup of black coffee our mother brought him.