“I am known to night and horses and the desert, to sword and lance, to parchment and pen.”

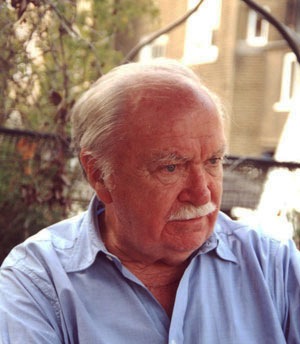

(George T. Scanlon, noted historian of Islamic art and architecture, was born April 23, 1925 and died July 13, 2014)

George Scanlon entered my life well before I actually met him in 1999. It was at a party on the balcony of an old Citadel flat where the minarets of Rifai and Sultan Hassan rose like masts from the sea of the Old City. I told him I’d followed his work while ghostwriting a Gulf princeling’s papers for the Islamic art and architecture graduate course George taught at the American University in Cairo. His tutelage, even second-hand, inspired a fascination with the medieval city that confirmed what I’d always suspected: Cairo was not a city but a universe.

I will not detail George’s long and distinguished academic career, but highlights include Swarthmore, where he studied history and literature, Palestine, where he taught at a boys’ school for two years, Princeton where he obtained his doctorate and conversed with Albert Einstein, and Egypt, where he directed the American Research Center and conducted excavations in Nubia and at Fustat. Suffice to say that George’s research, writing and teaching (he was a tenured professor at AUC from 1975-2011) helped ignite scholarly and public interest in the study and conservation of Egypt’s Islamic treasures, a legacy long overshadowed by its pharaonic ones. In time I understood that George saw Egypt as a consummate teacher, possessing an inexhaustible store of knowledge and infinite ways of conveying it.

Like many of us, he admired in others the qualities he felt that he possessed. George respected indomitability which is why he loved Egyptians. ‘We lived in the Depression, we didn’t have it’ he said of his childhood in Pennsylvania. He held his mother’s fortitude (and that of women in general) in high regard. When his father died of cancer, she raised six children and taught them to read by circling letters on a newspaper. His brother Will was blinded in an accident aged six but nonetheless went on to complete university. George found the notion of pharmaceutical remedies for sadness both fascinating and facile and called the blues ‘an easy road to a desired failure’. ‘Tell me Maria’ he asked, with a friendly scowl, ‘did you ever for a minute think that the world owed you a living?’ I confessed I had, but only for a minute.

Not everyone’s death heralds the end of an era, but George’s does, and he knew it would. He was looking scampish one night in 2007, with a bit of a beard and his arm in a cast, at a dinner in the Zamalek home of Salima Ikram and Nick Warner honoring Elizabeth and John Rodenbeck, his old friends and colleagues. ‘I won’t be around much longer’ he said matter-of-factly, looking at John, with whom he’d been reciting a Gerald Manley Hopkins poem a moment before, ‘but when we go there won’t be anything like us. It ends here.’

This remark was neither vain nor sentimental. George belonged to an ever-receding era when intellectual accomplishment meant learning both deep and broad, of history, philosophy, science and the arts. Erudition mattered nothing if unmatched by self-examination alongside the penetrating observation of one’s culture, surroundings and companions. Students of humanity of this caliber have grown understandably rare in a world that barely values them. Far from old-fashioned, George was the prototypical action-hero scholar/archeologist, an equestrian, student of war, bon vivant and intrepid traveler with a poetic sensibility, an astonishing memory and a wicked wit. Although gallant and declamatory, George did not perform so much as participate in his encounters with an enthusiasm that made his company deliciously provocative. ‘I am a spectator’ he said, ‘Show me something to applaud.’

I looked forward to our luncheons at the Bistro downtown or the Pub in Zamalek where he ordered for us both (as if preparing the meal himself) consulting me only on the color of the wine. Conversation during those three or four hour feasts might range from the 1001 Nights to a documentary about ballet he’d seen or something he’d read or heard at the Cairo opera. Politics came up. In 2005, shortly after Hosni Mubarak became president for his fifth term, he asked, ‘When do you think it will explode?’, nor was he surprised or put out when it finally did. George had no desire to leave Egypt. He wanted to see how things turned out.

George exalted in beauty, whether he found it in Maria Callas’ voice, the curve of a dancer’s neck or the soffit of a noble arch. He was something of a dandy, always handsomely turned out. The last time we met, he wore a grey pinstripe seersucker suit. What did we talk about that day? His 89th birthday was coming up and wishing to congratulate him, I said he’d never know the influence he’d had in others’ lives. He modestly changed the subject. But I nonetheless managed to insert a few fervent, if playful words, regarding how I felt about him, his spirit, its place in my world and in history. We didn’t speak about death per se, but adventure: our adventurousness in life as preparation for the greatest of all adventures, the beauty of belonging, once and for all, to eternity, of seeing all history spread out in a singe flash of comprehension. His pale blue eyes sparkled. I left him heading towards Bab el Louk beneath a blazing sun where he intended I think, to buy coffee. I intended to go home and nap. I looked back at him thinking: indomitable.

Now I will miss how he said my name, punching out the syllables like the title of some defunct deity: Myrhh-Ri-Ah. I will miss his essence, something finely human that is slipping through our hands; I believe it is called ‘civilization’. He left a message on my answering machine before flying to America earlier this year. ‘While I’m gone’ he said ‘be sure and try to have a good time. I know it will be difficult. But we must take the world in stride.’

AMIN, dear friend, and Godspeed!